John Landis

John Landis | |

|---|---|

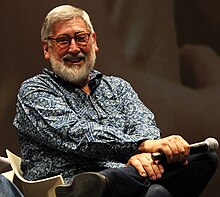

Landis at the 2022 Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Italy | |

| Born | John David Landis August 3, 1950 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1969–present |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Max Landis |

| Signature | |

| |

John David Landis (born August 3, 1950)[1] is an American filmmaker and actor. He is best known for directing comedy films such as The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977), National Lampoon's Animal House (1978), The Blues Brothers (1980), Trading Places (1983), Three Amigos (1986), Coming to America (1988) and Beverly Hills Cop III (1994), and horror films such as An American Werewolf in London (1981) and Innocent Blood (1992). He also directed the music videos for Michael Jackson's "Thriller" (1983) and "Black or White" (1991).

Landis later ventured into television work, including the series Dream On (1990), Weird Science (1994) and Sliders (1995). He also directed several episodes of the 2000s horror anthology series Masters of Horror and Fear Itself, as well as commercials for DirecTV, Taco Bell, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Kellogg's and Disney. In 2008, Landis won an Emmy Award for the documentary Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project (2007).

In 1982, Landis became the subject of controversy when three actors, including two children, died on set while filming his segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). Landis, as well as several other parties, were subsequently tried and acquitted for involuntary manslaughter, but the incident had long-lasting effects on film industry practices.

Landis is the father of filmmaker Max Landis.

Early life

[edit]Landis was born into a Jewish American family[2] in Chicago, Illinois, the son of Shirley Levine (née Magaziner) and Marshall Landis, an interior designer and decorator.[3] Landis and his parents relocated to Los Angeles when he was four months old. Though spending his childhood in California, Landis still refers to Chicago as his home town; he is a fan of the Chicago White Sox baseball team.[citation needed]

When Landis was a young boy, he watched The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, which inspired him to become a director:

I had complete suspension of disbelief—really, I was eight years old and it transported me. I was on that beach running from that dragon, fighting that Cyclops. It just really dazzled me, and I bought it completely. And so, I actually sat through it twice and when I got home, I asked my mom, "Who does that? Who makes the movie?"[4][5]

Career

[edit]Early

[edit]Landis began his film career working as a mailboy at 20th Century-Fox. He worked as a "go-fer" and then as an assistant director during filming Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's Kelly's Heroes in Yugoslavia in 1969; he replaced the film's original assistant director, who became ill and was sent home.[6] During that time Landis became acquainted with actors Don Rickles and Donald Sutherland, both of whom would later work in his films. Following Kelly's Heroes, Landis worked on several films that were shot in Europe (especially in Italy and the United Kingdom), including Once Upon a Time in the West, El Condor and A Town Called Bastard (a.k.a. A Town Called Hell).[6] Landis also worked as a stunt double.

I worked on some [pirate] movies, all kind of movies. French foreign movies. I worked on a movie called Red Sun where Toshiro Mifune kills me, puts a sword through me. ... I worked as a stunt guy. I worked as a dialogue coach. I worked as an actor. I worked as a production assistant.[6]

Aged 21, Landis made his directorial debut with Schlock. The film, which he also wrote and appeared in, is a tribute to monster movies.[6] The gorilla suit for the film was made by Rick Baker—the beginning of a long-term collaboration between Landis and Baker. Though completed in 1971, Schlock was not released until 1973 after it caught the attention of Johnny Carson. A fan of the film, Carson invited Landis on The Tonight Show and showed clips to help promote it. Schlock has since gained a cult following, but Landis has described the film as "terrible".[7]

Landis was hired by Eon Productions to write a screen treatment for The Spy Who Loved Me, but his screenplay of James Bond foiling a kidnapping of the Pope in Latin America was rejected by Albert R. Broccoli for satirizing the Catholic Church.[8] Landis was then hired to direct The Kentucky Fried Movie after David Zucker saw his Tonight Show appearance.[7] The film was inspired by the satirical sketch comedy of shows like Monty Python, Free the Army, The National Lampoon Radio Hour and Saturday Night Live.[6] It is notable for being the first film written by the Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker team, who would later have success with Airplane! and The Naked Gun trilogy.

1978–1981

[edit]Sean Daniel, an assistant to Universal executive Thom Mount, saw The Kentucky Fried Movie and recommended Landis to direct Animal House based on that. Landis says of the screenplay, "It was really literally one of the funniest things I ever read. It had a nasty edge like National Lampoon. I told him it was wonderful, extremely smart and funny, but everyone's a pig for one thing."[9] While Animal House received mixed reviews, it was a massive financial success, earning over $120 million at the domestic box office, making it the highest grossing comedy film of its time.[10][11] Its success started the "gross-out" film genre, which became one of Hollywood's staples. It also featured the screen debuts of John Belushi, Karen Allen and Kevin Bacon.

In 1980, Landis co-wrote and directed The Blues Brothers, a comedy starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd. It featured musical numbers by R&B and soul legends James Brown, Cab Calloway, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles and John Lee Hooker. It was, at the time, one of the most expensive films ever made, costing almost $30 million (for comparison, Steven Spielberg's contemporary film 1941 cost $35 million). It is speculated that Spielberg and Landis engaged in a rivalry, the goal of which was to make the more expensive film.[6] The rivalry might have been a friendly one, as Spielberg makes a cameo appearance in Blues Brothers (as the unnamed desk clerk near the end) and Landis had made a cameo in 1941 as a messenger.

In 1981, Landis wrote and directed another cult-status film, the comedy-horror An American Werewolf in London. It was perhaps Landis' most personal project; he had been planning to make it since 1969, while in Yugoslavia working on Kelly's Heroes. It was another commercial success for Landis and inspired studios to put comedic elements in their horror films.

Twilight Zone deaths and legal action against Landis

[edit]On July 23, 1982, during the filming of Twilight Zone: The Movie, actor Vic Morrow and child actors Myca Dinh Le (age 7) and Renee Shin-Yi Chen (age 6) were killed in an accident involving an out-of-control helicopter. The three were caught under the aircraft when it crashed, and Morrow and one child were decapitated.[12]

In June 1983, Landis, associate producer George Folsey Jr., production manager Dan Allingham, head of special effects Paul Stewart and helicopter pilot Dorcey Wingo were charged with involuntary manslaughter.[13] In December, Morrow's daughters Jennifer Jason Leigh and Carrie Morrow also sued Landis, Wingo, Warner Bros. Studios and others for negligence and wrongful death, resulting in Warner Bros. settling their case out of court, awarding $850,000 to each party.[14] Following the accident, Spielberg ended his friendship with Landis.[15][16]

In October 1984, the National Transportation Safety Board reported:

The probable cause of the accident was the detonation of debris-laden high temperature special effects explosions too near a low-flying helicopter leading to foreign object damage to one rotor blade and delamination due to heat to the other rotor blade, the separation of the helicopter's tail rotor assembly, and the uncontrolled descent of the helicopter. The proximity of the helicopter to the special effects explosions was due to the failure to establish direct communications and coordination between the pilot, who was in command of the helicopter operation, and the film director, who was in charge of the filming operation.[17]

The lawsuit finally proceeded in 1985.[18] Landis insisted that the deaths of Morrow, Le and Chen were the result of an accident.[19] However, camera operators filming the scene testified to Landis being a very imperious director, and a "yeller and screamer" on set.[20] During a take three hours before the incident, Wingo (a veteran of the Vietnam War) told Landis that the fireballs were too large and too close to the helicopter, to which Landis responded, "You ain't seen nothing yet."[21] With special effects explosions blasting around them, the helicopter descended over Morrow, Le, and Chen. Witnesses testified that Landis was still shouting for the helicopter to fly "Lower! Lower!" moments before it crashed.[22]

The prosecutors demonstrated that Landis was reckless and had not warned the parents, cast or crew of the children's and Morrow's proximity to explosives, or of limitations on their working hours.[12] He admitted that he had violated California law regulating the employment of children by using the children after hours, and conceded that that was wrong, but still denied culpability.[12] Numerous members of the film crew testified that the director was warned of the extreme hazard by technicians but ignored them.[citation needed] Metallurgist Gary Fowler testified that the heat from two explosions engulfed and delaminated the helicopter's tail rotor, causing it to fall off, and that there had been "no historical basis" for the phenomenon.[23]

Deputy District Attorney Lea Purwin D'Agostino stated that Landis was acting "cool", "slippery" and "glib" during the trial, and that his testimony contained inconsistencies.[21] After a ten-month jury trial that took place in 1986 and 1987, Landis—represented by criminal defense attorneys Harland Braun and James F. Neal—and the other crew members were acquitted of the charges.[24][25][26]

Both Le's and Chen's parents later filed civil suits against Landis and other defendants and eventually settled out of court with the studio for $2 million per family.[27] In 1988, Landis was reprimanded by the Directors Guild of America for unprofessional conduct on the set of the film and the California Labor Commission fined him $5,000 for violating child labor laws.[15] Additionally, Cal/OSHA issued 36 citations and $62,375 in fines, although this amount was later reduced to $1,350.[15] Warner Bros. vice president John Silvia also spearheaded a committee to create new safety standards for the film industry.[18]

During an interview with journalist Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan, Landis said, "When you read about the accident, they say we were blowing up huts—which we weren't—and that debris hit the tail rotor of the helicopter—which it didn't. The FBI Crime Lab, who was working for the prosecution, finally figured out that the tail rotor delaminated, which is why the pilot lost control. The special effects man who made the mistake by setting off a fireball at the wrong time was never charged."[6]

Subsequent film career

[edit]Trading Places, a Prince and the Pauper–style comedy starring Dan Aykroyd and Eddie Murphy, was filmed directly after the Twilight Zone accident. After filming ended, Landis and his family went to London. The film, a big hit at the box office (the 4th-most-popular movie of 1983) did well enough for Landis' image and career to improve, along with his involvement with Michael Jackson's "Thriller".

Next, Landis directed Into the Night, starring Jeff Goldblum, Michelle Pfeiffer and David Bowie, and appeared in the film, which was inspired by Hitchcock productions, as an Iranian hitman. To promote the film, Landis collaborated with Jeff Okun to direct a documentary film called B.B. King "Into the Night".

His next film, Spies Like Us (starring co-writer Dan Aykroyd and Chevy Chase), was an homage to the Road to ... films of Bob Hope and Bing Crosby. It was the 10th-most-popular movie of 1985. Hope made a cameo in the Landis film, portraying himself.[28]

In 1986, Landis directed Three Amigos, which featured Chevy Chase, Martin Short and Steve Martin. He then co-directed and produced the 1987 satirical comedy film Amazon Women on the Moon, which parodies the experience of watching low-budget films on late-night television.

Landis next directed the 1988 Eddie Murphy film Coming to America, which was hugely successful, becoming the third-most-popular movie of 1988 at the U.S. box office. It was also the subject of Buchwald v. Paramount, a civil suit filed by Art Buchwald in 1990 against the film's producers. Buchwald claimed that the concept for the film had been stolen from a 1982 script that Paramount optioned from Buchwald, and won the breach of contract action.[29]

In 1991, Landis directed Sylvester Stallone in Oscar, based on a Claude Magnier stage play. Oscar recreates a 1930s-era film, including the gestures along with bit acts and with some slapstick, as an homage to old Hollywood films.[30] In 1992, Landis directed Innocent Blood, a horror-crime film. In 1994, Landis directed Eddie Murphy in Beverly Hills Cop III, their third collaboration following Trading Places and Coming to America. In 1996, he directed The Stupids and then returned to Universal to direct Blues Brothers 2000 in 1998 with John Goodman and, for the fifth time in a Landis film, Dan Aykroyd, who also appeared in Landis' film Susan's Plan, released that same year. None of the above six films scored well with critics or audiences.

Burke and Hare was released in 2010, as Landis' first theatrical release in 12 years.

In August 2011, Landis said he would return to horror and would be writing a new film.[31] He was the executive producer on the comedy horror film Some Guy Who Kills People.

Music videos

[edit]Landis has directed several music videos. He was approached by Michael Jackson to make a video for his song "Thriller".[6] The resulting video significantly impacted MTV and the concept of music videos; it has won numerous awards, including the Video Vanguard Award for The Greatest Video in the History of the World. In 2009 (months before Jackson died), Landis sued the Jackson estate in a dispute over royalties for the video; he claimed to be owed at least four years' worth of royalties.[32][33]

In 1991, Landis collaborated again with Michael Jackson on the music video for the song "Black or White".

Television

[edit]Landis has been active in television as the executive producer (and often director) of the series Dream On (1990), Weird Science (1994), Sliders (1995), Honey, I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Show (1997), Campus Cops (1995), The Lost World (1998), Masters of Horror, and various episodes of Psych. He also made commercials for DirecTV, Taco Bell, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Kellogg's, and Disney. In 2011 he made an appearance in Reece Shearsmith and Steve Pemberton's television series Psychoville. In June 2020, Landis signed on to direct and executive produce the streaming series Superhero Kindergarten.[34]

Documentaries

[edit]Landis made his first documentary, Coming Soon, in 1982; it was only released on VHS. In 1983, he worked on the 45-minute documentary Making Michael Jackson's Thriller, which aired on MTV and Showtime and was simultaneously released on home video, which became the biggest selling home video release of the time.[35] Next, he co-directed B.B. King "Into the Night" (1985) and in 2002 directed Where Are They Now?: A Delta Alumni Update, which can be seen as a part of the Animal House DVD extras. Initially, his documentaries were only made to promote his feature films. Later in his career he became more serious about the oeuvre and made Slasher (2004), Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project (2007) and Starz Inside: Ladies or Gentlemen (2009) for television. Landis won a 2008 Emmy Award for Mr. Warmth.[36] In 2023, he appeared in the Spanish documentary The Man Who Saw Frankenstein Cry, which covered the career of Spanish movie director Paul Naschy.[37] Landis was friends with Christopher Lee and he appeared in the documentary The Life and Deaths of Christopher Lee (2024).[38]

Archives

[edit]Landis' moving image collection is held at the Academy Film Archive.[39] The film material at the Archive is complemented by photographs, artwork and posters found in Landis' papers at the Academy's Margaret Herrick Library.[40]

Personal life

[edit]Landis is married to Deborah Nadoolman, a costume designer. They have two children: Max and Rachel. In a BBC Radio interview, he stated that he is an atheist.[41] The family lives in Beverly Hills, California.[42] They had purchased Rock Hudson's estate in Beverly Crest after the actor died there from complications of AIDS. The property was later sold to Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.[43]

In 2009, Landis signed a petition in support of director Roman Polanski, who had been detained while traveling to a film festival in relation to his 1977 sexual abuse charges, which the petition argued would undermine the tradition of film festivals as a place for works to be shown "freely and safely", and that arresting filmmakers traveling to neutral countries could open the door "for actions of which no-one can know the effects."[44][45]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Producer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Schlock | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1977 | The Kentucky Fried Movie | Yes | No | No | |

| 1978 | Animal House | Yes | No | No | a.k.a. National Lampoon's Animal House |

| 1980 | The Blues Brothers | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1981 | An American Werewolf in London | Yes | Yes | No | |

| 1982 | Coming Soon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Documentary |

| 1983 | Trading Places | Yes | No | No | |

| Twilight Zone: The Movie | Yes | Yes | Yes | Segments "Prologue" and "Time Out" | |

| 1985 | Into the Night | Yes | No | No | plus actor, as one of the Iranian henchmen |

| Spies Like Us | Yes | No | No | ||

| Clue | No | Story | Executive | Co-story with Jonathan Lynn | |

| 1986 | ¡Three Amigos! | Yes | No | No | |

| 1987 | Amazon Women on the Moon | Yes | No | Executive | Segments "Mondo Condo", "Hospital", "Blacks Without Soul" and "Video Date" |

| 1988 | Coming to America | Yes | No | No | |

| 1991 | Oscar | Yes | No | No | |

| 1992 | Innocent Blood | Yes | No | No | |

| 1994 | Beverly Hills Cop III | Yes | No | No | |

| 1996 | The Stupids | Yes | No | No | |

| 1998 | Blues Brothers 2000 | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Susan's Plan | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| 2010 | Burke and Hare | Yes | No | No |

Executive producer

- The Lost World (1998)

- Some Guy Who Kills People (2012)

- I Hate Kids (2019)

Acting roles

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Kelly's Heroes | Sister Rosa Stigmata | Uncredited; Also production assistant |

| 1973 | Battle for the Planet of the Apes | Jake's Friend | |

| Schlock | Schlock | ||

| 1975 | Death Race 2000 | Mechanic | |

| 1977 | The Kentucky Fried Movie | TV Technician | Uncredited |

| 1979 | The Muppet Movie | Grover | Uncredited, puppetry only in Rainbow Connection Finale scene |

| 1941 | Mizerany | ||

| 1980 | The Blues Brothers | Trooper La Fong | |

| 1981 | An American Werewolf in London | Man Being Smashed Into Window | Uncredited |

| 1982 | Eating Raoul | Man who bumps into Mary | |

| 1983 | Trading Places | Man with briefcase | |

| 1984 | The Muppets Take Manhattan | Leonard Winesop | |

| 1985 | Into the Night | SAVAK | plus director |

| 1990 | Spontaneous Combustion | Radio Technician | |

| Darkman | Physician | ||

| 1992 | Sleepwalkers | Lab Technician | |

| Body Chemistry II: Voice of a Stranger | Dr. Edwards | ||

| Venice/Venice | Himself | ||

| 1994 | The Silence of the Hams | FBI Agent | |

| 1996 | Vampirella | Astronaut #1 | |

| 1997 | Laws of Deception | Judge Trevino | |

| Mad City | Doctor | ||

| 1999 | Diamonds | Gambler | |

| Freeway II: Confessions of a Trickbaby | Judge | ||

| 2004 | Surviving Eden | Doctor Levine | |

| Spider-Man 2 | Doctor | ||

| 2005 | The Axe | Père copain Maxime | |

| Torrente 3: El protector | Embajador árabe | ||

| 2007 | Look | Aggravated Director | |

| 2012 | Attack of the 50 Foot Cheerleader | Professor | |

| 2015 | Wrestling Isn't Wrestling | Therapist | Short film |

| 2015 | Tales of Halloween | Jebediah Rex | Segment "The Ransom of Rusty Rex" |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Producer | Writer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | Holmes & Yo-Yo | No | No | Story | Episode "Key Witness" |

| 1985 | Disneyland's 30th Anniversary Celebration | Yes | No | No | TV documentary |

| George Burns Comedy Week | Yes | No | No | Episode "Disaster at Buzz Creek" | |

| 1990–1996 | Dream On | Yes | Executive | No | Directed 17 episodes |

| 1990 | Disneyland's 35th Anniversary Celebration | Yes | No | No | TV documentary |

| 1994 | Weird Science | No | Executive | No | |

| 1995 | Sliders | No | Executive | No | |

| 1996 | Campus Cops | Yes | Executive | No | Directed episodes "Muskrat Ramble" and "3,001" |

| 1997–1999 | Honey, I Shrunk the Kids: The TV Show | Yes | Executive | No | Directed episode "Honey, Name That Tune" |

| 1999–2002 | The Lost World | No | Executive | No | |

| 2002 | The Kronenberg Chronicles | Yes | Executive | No | Unaired pilot |

| 2004 | Slasher | Yes | No | No | Television documentary |

| 2005–2006 | Masters of Horror | Yes | No | Yes | Directed and co-wrote episode "Deer Woman" Directed episode "Family" |

| 2007 | Mr. Warmth: The Don Rickles Project | Yes | Yes | No | TV documentary |

| 2007–2008 | Psych | Yes | No | No | 3 episodes |

| 2008 | Fear Itself | Yes | No | No | Episode "In Sickness and in Health" |

| Starz Inside: Ladies or Gentlemen | No | Executive | No | TV documentary | |

| 2011 | Wendy Liebman: Taller on TV | No | Yes | No | Stand-up special |

| 2012 | Franklin & Bash | Yes | No | No | Episode "Voir Dire" |

| 2021 | Superhero Kindergarten | Yes | Executive | No | 26 episodes[34] |

Acting roles

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | The Six Million Dollar Man | Michael | Episode "The Pal-Mir Escort" |

| 1990 | Psycho IV: The Beginning | Mike Calveccio | TV movie |

| 1991–1994 | Dream On | Herb | Episodes "Futile Attraction" and "Where There's Smoke, You're Fired" |

| 1994 | The Stand | Russ Dorr | Episode "The Stand" |

| 2011 | Psychoville | Director | Episode "Dinner Party" |

Music videos

[edit]| Year | Title | Artist |

|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Thriller | Michael Jackson |

| 1985 | My Lucille | B.B. King |

| Into the Night | ||

| In the Midnight Hour | ||

| 1986 | Spies Like Us | Paul McCartney |

| 1991 | Black or White | Michael Jackson |

Unrealized projects

[edit]| Year | Title and description | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 1970s | See You Next Wednesday, a fictional "musical autobiography" of himself if he died at 19 years old | [46] |

| Teenage Vampire, a vampire film set in 1950s Ohio | [47] | |

| The Spy Who Loved Me | [48][49] | |

| Close Encounters of the Third Kind, retitled from Project Bluebook | [50] | |

| The Thing | [51] | |

| The Incredible Shrinking Woman | [52][53] | |

| A film adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's novel The Lost World | [54] | |

| 1980s | Barnum, a biopic of circus showman P. T. Barnum written by Bill Lancaster starring John Belushi | [55][56] |

| Dick Tracy starring Clint Eastwood | [57][58] | |

| Clue | [59] | |

| A Chorus Line | [60] | |

| Little Shop of Horrors | [61] | |

| Club Paradise | [62] | |

| The Lone Ranger, a film based on the eponymous character written by George MacDonald Fraser | [63] | |

| 1990s | A remake of the 1933 film King Kong | [64][65] |

| Red Sleep, a vampire film with Mick Garris, Richard Christian Matheson and Harry Shearer set in Las Vegas | [66][58][67] | |

| A sequel to his film An American Werewolf in London | [68] | |

| An unaired TV pilot based on Thorne Smith's novel Topper, starring Tim Curry, Courteney Cox and Ben Cross | [69][70] | |

| Call Me a Cop, a comedy about a group of gangsters who disguise themselves as policemen | [71][72] | |

| The Return of Willard, a sequel to Willard starring Bruce Davison | [73] | |

| A film adaptation of Mark Twain's novel A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court | [74][75] | |

| 2000s | Really Scary, an anthology horror film with segments directed by Landis, Guillermo del Toro, Sam Raimi and Joe Dante | [76] |

| Gone, a thriller set in a haunted house | [77][78][79] | |

| A film adaptation of Keythe Farley and Brian Flemming's rock musical Bat Boy | [80][48] | |

| A film adaptation of Larry Coen and David Crane's one-act play Epic Proportions written by Todd Berger | [81][50] | |

| The Missionary Position, retitled from Missionary Impossible, a comedy written by Glen Brackenridge and Curtis Brien | [82][50][83] | |

| Show Dogs, a comedy about a homeless Jack Russell Terrier written by Mike Bender | [82][48] | |

| The Wolfman | [84] | |

| Ghoulishly Yours, William M. Gaines, a biopic of EC Comics publisher William Gaines written by Joel Eisenberg | [85][86] | |

| The Bone Orchard, a Western about Chinese vampires | [87] | |

| A film adaptation of Richard Brinsley Sheridan's five-act play The Rivals starring Joseph Fiennes and Albert Finney | [87][88] | |

| 2010s | Untitled monster movie with Alexandre Gavras set in Paris | [31][89][90] |

| 2020s | Superhero Kindergarten live-action TV series | [34] |

| Untitled Superhero Kindergarten film spin-off |

References

[edit]- ^ "John Landis - Biography, Movie Highlights and Photos - AllMovie". Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ Bloom, Nate (February 2, 2012). "Jewish stars: Whales, ghosts and 'Smash'". Cleveland Jewish News.

- ^ "John Landis". yahoo.com. Yahoo! Movies.

- ^ As told to Robert K. Elder for The Film That Changed My Life

- ^ Landis, John. Interview by Robert K. Elder. The Film That Changed My Life. By Robert K. Elder. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011. N. p. 223. Print.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan (2008). John Landis. M Press. ISBN 978-1-59582-041-9.

- ^ a b filmSCHOOLarchive (May 6, 2018), John Landis on "Schlock" & "Kentucky Fried Movie", archived from the original on December 21, 2021, retrieved February 23, 2019

- ^ Field, Matthew (2015). Some kind of hero : 007 : the remarkable story of the James Bond films. Ajay Chowdhury. Stroud, Gloucestershire. ISBN 978-0-7509-6421-0. OCLC 930556527.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Cheney, Alexandra (February 25, 2014). "John Landis on Harold Ramis: He Was Very Angry Not to Be Cast in 'Animal House'". Variety. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ "National Lampoon's Animal House (1978) - Box Office Mojo". Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ "Animal House: The Movie that Changed Comedy | Stumped Magazine". Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ a b c Farber, Stephen; Green, Marc (1988). Outrageous Conduct: Art, Ego and the Twilight Zone Case. Arbor House (Morrow). ISBN 978-0877959489.

- ^ Matthews, Jay (June 25, 1983). "Landis Pleads Not Guilty". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 28, 2017. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ "Vic Morrow's daughters settle lawsuit". United Press International. December 29, 1983. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c Farber, Stephen; Green, Marc (August 28, 1988). "TRAPPED IN THE TWILIGHT ZONE: A Year After the Trial, Six Years After the Tragedy, the Participants Have Been Touched in Surprisingly Different Ways". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ^ Kirchner, Lisa (January 19, 2012). "An Interview with Director John Landis". cineAWESOME!. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ Airplane disaster report[usurped]

- ^ a b Weintraub, Robert (July 26, 2012). "A New Dimension of Filmmaking". Slate. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Doyle, James J. (June 24, 1983). "Director John Landis and four assistants pleaded innocent Friday". United Press International. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ UPI (November 2, 1986). "FILM DEATHS WITNESS TESTIFIES SAFETY WAS IGNORED". The New York Times. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ a b Deutsch, Lina (February 23, 1987). "Prosecution Tries to Shake Landis' 'Twilight Zone' Testimony". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 29, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Harris, Michael D. (October 2, 1986). "The parents of two children killed on the 'Twilight..." United Press International. Retrieved July 30, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Michael D. (March 9, 1987). "Special effects caused fatal helicopter crash, witness says". United Press International. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Cummings, Judith (May 30, 1987). "ALL 5 ACQUITTED IN 3 DEATHS ON FILM SET". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Noe, Denise. "The Twilight Zone Tragedy". crimelibrary.org. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Weber, Bruce (October 22, 2010). "James F. Neal, Litigated Historic Cases, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 21, 2023. Retrieved May 22, 2024.

- ^ Feldman, Paul (June 3, 1987). "Settlements Reported in Two Families' Civil Suits Over 'Twilight Zone' Deaths". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 21, 2024.

- ^ Spies Like Us (1985) - IMDb, retrieved December 2, 2020

- ^ Buchwald v. Paramount, C 706083 Tentative Decision (Second Phase), III.B.5 Unconscionability—The Doctrine Applied (Los Angeles County Superior Court December 21, 1990).

- ^ Landis, John (April 26, 1991), Oscar (Comedy, Crime), Sylvester Stallone, Ornella Muti, Peter Riegert, Chazz Palminteri, Joseph S. Vecchio Entertainment, Silver Screen Partners IV, Touchstone Pictures, retrieved December 2, 2020

- ^ a b Eggertsen, Chris (August 10, 2011). "John Landis Tells B-D He's Making Another Monster Movie!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Legal Thriller: Michael Jackson Sued by John Landis Yahoo News, January 27, 2009

- ^ "Michael Jackson sued by 'Thriller' director". NME. January 27, 2009.

- ^ a b c Jennings, Collier (June 20, 2020). "John Landis to Direct Stan Lee's Superhero Kindergarten Starring Schwarzenegger". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- ^ Griffin, Nancy (July 2010). "The "Thriller" Diaries". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 16, 2015.

- ^ "Meet the interviewer: John Landis". Directors Guild of America. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ "Naschy Documentary to Debut This Fall". May 18, 2023.

- ^ "Sir Christopher Lee documentary to tell untold story of actor's life". BBC. May 7, 2024. Retrieved December 16, 2024.

- ^ "John Landis Collection". Academy Film Archive. August 20, 2015.

- ^ "John Landis Papers". Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- ^ "Interview: John Landis, conducted by Simon Mayo and Mark Kermode". Kermode and Mayo's Film Review, BBC Five Live. London. November 11, 2011. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ "John Landis' House in Beverly Hills, CA - Virtual Globetrotting". January 29, 2009.

- ^ Paynter, Sarah (July 13, 2021). "Rock Hudson estate listed for the first time in decades for $55.5M". New York Post. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ "Le cinéma soutient Roman Polanski / Petition for Roman Polanski - SACD". archive.ph. June 4, 2012. Archived from the original on June 4, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine; Agencies (September 29, 2009). "Release Polanski, demands petition by film industry luminaries". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- ^ Kluger, Bryan (June 8, 2018). "Director John Landis talks about Stanley Kubrick, Eddie Murphy, Michael Jackson, and more!" (video). YouTube. Bryan Kruger.

- ^ Alexander, Dave (2021). Untold Horror. Dark Horse Comics. pp. 37–39. ISBN 978-1506719023.

- ^ a b c Landis, John (September 1, 2005). "The Collider Interview: John Landis, Part II". Collider (Interview). Interviewed by Weintraub, Steve.

- ^ Gunning, Cathall (November 19, 2022). "Roger Moore's Wild, Unmade James Bond Movie About The Pope". Screen Rant. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Quint chats with John Landis about BLUES BROTHERS, BAT BOY, MOH and more!!!". Ain't It Cool News. August 29, 2005. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Lyttelton, Oliver (June 25, 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About John Carpenter's 'The Thing'". IndieWire. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog - The Incredible Shrinking Woman". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (January 29, 1981). "LILY TOMLIN:'SHRINKING WOMAN' STANDS TALL". The New York Times. p. 13. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Horowitz, Mark (director). Albert Whitlock: A Master of Illusion. Documentary film. 1980. KCET Productions.

- ^ Thoret, Jean-Baptiste (March 15, 2016). "JOHN LANDIS : Barnum | Jamais Sur Vos Écrans" (video). YouTube (in French). Créations originales - Forum des images.

- ^ "John Landis : « Avant les années 70, les réalisateurs inventaient le cinéma »". Le Monde (in French). March 15, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog - Dick Tracy". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Hemphill, Jim (October 3, 2017). ""Making a Hammer Film As If It Was Directed by Scorsese": John Landis on Innocent Blood and Operating Muppets with Tim Burton". Filmmaker. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (August 25, 1985). "OFF THE BOARD, ONTO THE SCREEN FOR CLUE". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Douglas, Illeana (June 12, 2018). "John Landis, Producer, Director, Actor – I Blame Dennis Hopper" (video). YouTube (Podcast). Popcorn Talk.

- ^ "Interview with Howard Ashman". Unknown Baltimore Publication. 1984. Archived from the original on April 12, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ^ Spears, Steve (July 11, 2016). "30 years later, 'Club Paradise' more bargain than all-inclusive comedy". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved January 1, 2024.

- ^ Buck, Jerry (July 20, 1990). "Landis fulfills HBO's dreams of gold". Chicago Sun-Times (FIVE STAR SPORTS FINAL ed.). p. 63.

- ^ LeMay, John (2019). Kong Unmade: The Lost Films of Skull Island. Bicep Books. p. 376. ISBN 978-1798077993.

- ^ Cates, Hunter (April 16, 2021). "King Kong Movies That Never Happened". Looper. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog - Innocent Blood". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Weinstein, Max (August 11, 2021). "Mick Garris Says These Unmade Scripts Are Among His Biggest Regrets". Dread Central. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Fletcher, Rosie (November 21, 2017). "John Landis planned a sequel to An American Werewolf in London – and it sounds amazing". Digital Spy. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Kleid, Beth (January 6, 1992). "TELEVISION". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "JOHN LANDIS DISCUSSES "INNOCENT BLOOD" AND HIS CAREER (1992)". Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ^ Moerk, Christian (December 9, 1993). "Mancuso lines up big MGM/UA guns". Variety. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Archerd, Army (July 19, 1994). "'Lies' convinces H'w'd to invest". Variety. Retrieved January 6, 2025.

- ^ Parajillo, Xanthe (July 22, 2020). "Tear It Up: Revisiting the Rat-Infested Cult of 'Willard'". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ Barber, Nicholas (May 9, 1998). "ARTS: CINEMA: The Blues Brothers just get younger". The Independent. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ "Chat Transcript: Director John Landis on Home Theater Forum". The Digital Bits. October 24, 2001. Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved December 29, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Untold Horror Trailer" (video). YouTube. Kevin Burke. February 22, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Hettrick, Scott (June 22, 2004). "Dark Horse, Image ride together". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Hettrick, Scott (November 6, 2005). "Indie shingles 'Gone' wild". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Gustins, George Gene (November 12, 2005). "A Quirky Superhero of the Comics Trade". The New York Times. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Wolf, Matt (December 5, 2004). "Landis wings to 'Bat Boy'". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Broadway.com Staff (December 14, 2004). "Coen and Crane's Epic Proportions to Get the Hollywood Treatment". Broadway.com. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Fritz, Ben (July 31, 2005). "Landis takes 'Dogs' leash". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Gardner, Chris (December 15, 2005). "Landis lines up for 'Missionary'". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (February 1, 2008). "COLLIDER EXCLUSIVE: John Landis for WOLF MAN?". Collider. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ McNary, Dave (February 14, 2008). "Landis to direct 'Ghoulishly Yours'". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Adler, Tim (May 15, 2010). "CANNES: John Landis Developing Biopic Of 1950s EC Comics Crusader William Gaines". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ a b Jaafar, Ali (November 6, 2008). "John Landis returns to directing". Variety. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Pollak, Kevin (August 1, 2011). "KPCS: John Landis #121" (video). YouTube. kevinpollakchatshow.

- ^ Uddin, Zakia (August 10, 2011). "John Landis to make French horror". Digital Spy. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ Wright, Benjamin (October 10, 2012). "John Landis Says Fox Doesn't Love Max Landis' 'Chronicle 2' Script, His Paris-Set Monster Movie Is Dead For Now & Talks Hardships Of 'American Werewolf'". IndieWire. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alberto Farina (1995). John Landis. Il Castoro. ISBN 978-88-8033-030-1

- Giulia D'Agnolo Vallan (2008). John Landis. M Press. ISBN 1-59582-041-8

External links

[edit]- John Landis at IMDb

- 80's Movie Rewind Profile about Director

- Daily Variety, May 24, 1994: Spotlight on John Landis — Billion Dollar Director Archived October 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Interviews

- About Twilight Zone accident

- 1950 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American Jews

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- 21st-century American Jews

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American screenwriters

- American atheists

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American male video game actors

- American male screenwriters

- American music video directors

- American television directors

- American comedy film directors

- Film directors from Illinois

- Film producers from Illinois

- American horror film directors

- Jewish American atheists

- Jewish film people

- Jewish American male actors

- Jewish American screenwriters

- Male actors from Chicago

- People acquitted of manslaughter

- Television producers from Illinois

- Screenwriters from Illinois