Battle of Almansa

| Battle of Almansa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

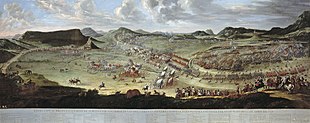

The Battle of Almansa by Ricardo Balaca | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The Battle of Almansa took place on 25 April 1707, during the War of the Spanish Succession. It was fought between an army loyal to Philip V of Spain, Bourbon claimant to the Spanish throne, and one supporting his Habsburg rival, Archduke Charles of Austria. The result was a decisive Bourbon victory that reclaimed most of eastern Spain for Philip.

The Bourbon army was commanded by the Duke of Berwick, illegitimate son of James II of England, while Habsburg forces were led by Henri de Massue, Earl of Galway, an exiled French Huguenot. This makes it "probably the only battle in history in which the English forces were commanded by a Frenchman, the French by an Englishman."[8]

Background

[edit]

Campaigning in Spain and size of the armies involved were limited by logistics to a greater extent than Flanders or Italy. Reliance on local sources for forage and other supplies limited operations in arid areas like Northern Spain, that until the advent of railways in the 19th century, goods and supplies were largely transported by water.[9] Control of the seas allowed the Allies to successfully conduct short-term offensives outside the coastal areas but lack of popular support meant they could not hold territory. The Grand Alliance secured an operations base in Lisbon when Peter II of Portugal changed sides in May 1703, and the following March, Archduke Charles of Austria arrived to head a land campaign.[10]

The Bourbon alliance between France and Spain won a series of minor victories along the Spanish-Portuguese border, offset by the British capture of Gibraltar; attempts to retake it were defeated at the naval Battle of Málaga in August 1704, with a land siege being abandoned in April 1705.[11] The 1705 'Pact of Genoa' between English and Catalan representatives opened a second front in the north-east; the Allied capture of Barcelona and Valencia left Toulon as the only major port available to the Bourbons in the Western Mediterranean.[12]

An attempt in May 1706 by Philip V of Spain to retake Barcelona failed, while his absence allowed an Allied force to capture Madrid and Zaragossa but they could not be resupplied so far from their bases and were forced to withdraw. By November 1706, Philip controlled the Crown of Castile, Murcia and parts of the Kingdom of Valencia.[12] Over the course of 1706, Allied victories in the Spanish Netherlands and Italy forced the French onto the defensive and Galway sought to take advantage by launching a new offensive in 1707. To counter this, James FitzJames, 1st Duke of Berwick, was appointed commander of Bourbon forces in North-East Spain, a total of 33,000 men, split equally between French and Spanish troops, with a number of exiled Irish regiments.[13]

Before beginning his advance on Valencia, Berwick detached 8,000 men to besiege Xàtiva, prompting the Earl of Peterborough, Allied commander in Spain, to consolidate his forces in Catalonia, rather than combine with the 16,500 troops led by Galway and Minas. This left them badly outnumbered when they moved to intercept Berwick.[2] On 22 April, Berwick halted outside the town of Almansa, from where he could threaten supply lines for the Allied garrison in Valencia.[13]

Battle

[edit]

The Allies broke camp early on 25 April and reached Almansa after a long and tiring march. Berwick had drawn up his army in two lines, just in front of the town, his infantry in the centre and the French and Spanish cavalry on the wings. Although Galway was clearly outnumbered, he commenced his attack in mid-afternoon after a short artillery exchange. His infantry successfully drove back the Bourbon centre but a gap opened between them and Portuguese troops on the right, under the 63-year-old Marquess of Minas. Seeing this, the Franco-Spanish cavalry attacked; Berwick's account states the Portuguese fought bravely for some time but eventually collapsed and fled. Their retreat was covered by a few squadrons under Das Minas' personal command, including his mistress, who fought dressed as a man and was killed.[14]

The Allied centre was now attacked on three sides; using his remaining cavalry, Galway successfully withdrew some of his troops but 13 battalions lost contact with the rest of the army. Pursued by the Spanish cavalry, they took up a defensive position some 8 miles (12 km) from the battlefield but surrendered the next morning; according to Henry Kamen, allied casualties were 4,000 killed or wounded and 3,000 captured, with Franco-Spanish losses around 5,000 killed or wounded.[2] French military historian Périni claimed Franco-Spanish casualties totalled around 2,000 killed or wounded, with the Allies losing 5,000 casualties and 10,000 prisoners, but from a larger force than 16,500 men. Périni also accepts the bulk of the cavalry escaped, some 3,500 men.[6] According to Gaston Bodart, the Franco-Spanish lost 2,000 men from an army of 21,000 and the allies 12,000 men (5,000 killed or wounded and 7,000 captured) from a force of 16,000.[3] Finally, according to Joaquim Albareda, the Bourbon forces lost 1,500 men, whereas total allied losses were around 7,000.[5]

Aftermath

[edit]Almansa has been described as "the single most important battle fought in Spain during the war".[15] Berwick's tactics were admired by many, Frederick the Great later describing it as the most impressive battle of the century. Victory confirmed Philip's control of North-East Spain and Valencia, while by the end of 1707 the Allies were once again restricted to Catalonia and the Balearic Islands.[2]

The Franco-Spanish army followed up their success by besieging Xàtiva; when it surrendered in June, much of the town was destroyed and its name changed to 'San Felipe.' In memory of these events, a portrait of the monarch still hangs upside down in the local museum. The defeat and its consequences for the autonomy of Valencia and Catalonia gave rise to two modern proverbs; "De ponent, ni vent ni gent," ('From the west, neither wind nor people') and Quan el mal ve d'Almansa, a tots alcança, ('Bad news from Almansa reaches everybody').

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Enschedé, A.J. (1896). "Jacques-Louis, Comte de Noyelles et de Fallais. Général au service des Provinces-Unies". Bulletin de la Commission pour l'histoire des églises Wallonnes (in French). Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 79–88. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kamen 2003, p. 445.

- ^ a b c d e Bodart 1908, p. 151.

- ^ La guerra de sucesión en Valencia (De bello rustico Valentino). José Manuel Miñana, Francisco Jorge Pérez Durá & José María Estellés i González, Real Instituto de Estudios Asturianos, 1985, pp. 183.

- ^ a b c Albareda Salvadó 2010, p. 223.

- ^ a b c De Périni 1896, p. 190.

- ^ Resumen de historia de España: con un breve compendio dialogado para los niños. Esteban Paluzíe y Cantalozella, Litogr. del autor, 1866, pp. 107.

- ^ Norwich 2007, p. 237.

- ^ Childs 1991, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Francis 1965, pp. 71–93.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 296.

- ^ a b Lynn 1999, p. 302.

- ^ a b De Périni 1896, p. 186.

- ^ Cavendish 2007.

- ^ Lynn 1999, p. 316.

Sources

[edit]- Cavendish, Richard (2007). "The Battle of Almanza". History Today. 57 (4).

- De Périni, Hardÿ (1896). Batailles françaises, Volume VI 1700–1782 (in French). Ernest Flammarion.

- Childs, John (1991). The Nine Years' War and the British Army, 1688–1697: The Operations in the Low Countries (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719089964.

- Francis, AD (1965). "Portugal and the Grand Alliance". Historical Research. 38 (97): 71–93. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1965.tb01638.x.

- Kamen, Henry (2003). Spain's Road to Empire: The Making of a World Power, 1492–1763. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140285284.

- Lynn, John (1999). The Wars of Louis XIV, 1667–1714. Longman. ISBN 978-0582056299.

- Norwich, John Jules (2007). The Middle Sea; A History of the Mediterranean. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-7608-2.

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon, (1618–1905).

- Albareda Salvadó, Joaquim (2010). La Guerra de Sucesión de España (1700–1714), (1618–1905). Editorial Crítica.

External links

[edit]- Conflicts in 1707

- Battles involving England

- Battles involving France

- Battles involving Portugal

- Battles involving Spain

- Battles involving the Dutch Republic

- Battles of the War of the Spanish Succession

- Military history of Castilla–La Mancha

- 1707 in France

- War of the Spanish Succession

- History of the province of Albacete

- Almansa

- Battles involving the Holy Roman Empire