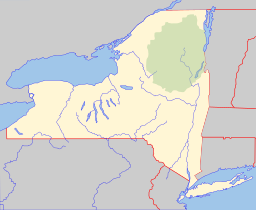

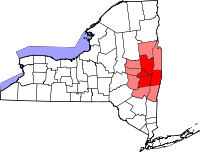

Lake George (lake), New York

| Lake George | |

|---|---|

Above Cook's Bay, facing south | |

| Location | Adirondack Mountains, Warren / Essex counties, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 43°37′20″N 73°32′48″W / 43.62222°N 73.54667°W |

| Primary inflows | Streams 55%, Precipitation on lake surface 27%, groundwater 18% |

| Primary outflows | La Chute River |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Max. length | 32.2 mi (51.8 km) |

| Max. width | 3 mi (4.8 km) |

| Surface area | 45 sq mi (120 km2) |

| Average depth | 70 ft (21 m) |

| Max. depth | 196 ft (60 m) |

| Water volume | .597 cu mi (2.49 km3) (88 billion cubic feet) |

| Surface elevation | 320 ft (98 m) |

| Islands | Over 170 (172-178) |

| Settlements | Lake George, Ticonderoga, Bolton Landing, Huletts Landing |

Lake George, nicknamed the Queen of American Lakes,[2] is a long, narrow oligotrophic lake located at the southeast base of the Adirondack Mountains, in the northeastern portion of the U.S. state of New York. It lies within the upper region of the Great Appalachian Valley and drains all the way northward into Lake Champlain and the St. Lawrence River drainage basin. The lake is situated along the historical natural (Amerindian) path between the valleys of the Hudson and St. Lawrence Rivers, and so lies on the direct land route between Albany, New York, and Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The lake extends about 32.2 mi (51.8 km) on a north–south axis, is 187 ft (57 m) deep,[3] and ranges from one to three miles (1.6 to 4.8 km) in width, presenting a significant barrier to east–west travel. Although the year-round population of the Lake George region is relatively small, the summertime population can swell to over 50,000 residents, many in the village of Lake George region at the southern end of the lake.[not verified in body]

Lake George drains into Lake Champlain to its north through a short stream, the La Chute River, with many falls and rapids, dropping 226 feet (69 m) in its 3.5-mile (5.6 km) course—virtually all of which is within the lands of Ticonderoga, New York, and near the site of Fort Ticonderoga. Ultimately the waters flowing via the 106-mile-long (171 km) Richelieu River drain into the St. Lawrence River downstream and northeast of Montreal, and then into the North Atlantic Ocean Nova Scotia.

Water quality

[edit]Lake George is rated Class AA-Special by New York State and is considered drinking water. Despite being one of the top ten cleanest lakes in the United States in 2023 and 2024, Lake George is also on New York's 303(d) list of impaired waterbodies.[4]

Geography

[edit]Lake George is located in the southeastern Adirondack State Park and is part of the St. Lawrence watershed. Notable landforms include Anthony's Nose, Deer's Leap, Peggy's Point (a 15-foot [4.6 m] jump into the lake) or (a 30-foot [9.1 m] jump), the Indian Kettles, and Roger's Rock.

Some of the surrounding mountains include Black Mountain, Elephant Mountain, Pilot Knob, Prospect Mountain, Shelving Rock, Sleeping Beauty Mountain, Sugarloaf Mountain, and the Tongue Mountain Range. Some of the lake's more famous bays are Basin Bay, Kattskill Bay, Northwest Bay, Oneida Bay, and Silver Bay.

The lake is distinguished by "The Narrows", an island-filled narrow section (approximately five miles [8 km] long) that is bordered on the west by the Tongue Mountain Range and the east by Black Mountain. In all, Lake George is home to over 170 islands, 148 of them state-owned. They range from the car-sized Skipper's Jib to the larger Vicar's and Long Islands. Camping permits are available for most islands.

The lake's deepest point is 196 feet (60 m), between Dome Island and Buck Mountain in the southern quarter of the lake. The northern end of the lake that is located near Ticonderoga is considered the southern end of the Champlain Valley, which includes Lake Champlain, as well as the cities Plattsburgh, New York, and Burlington, Vermont.

The Jefferson Project, a collaboration that began in 2014 between IBM, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, and the Fund for Lake George, is collecting data from the lake using depth sensors that can monitor currents, pH, salinity, and other data, leading the lake to be called, "[t]he smartest lake in the world."[5]

Invasive species

[edit]There are six known invasive species in Lake George. The Asian clam first found in 2010 is the biggest threat, along with the Eurasian watermilfoil. Other invasive species are the Chinese mystery snail, curly-leaf pondweed, spiny water flea, and zebra mussel.[6]

History

[edit]The lake was originally named the Andia-ta-roc-te by local Native Americans. James Fenimore Cooper in his narrative Last of the Mohicans called it the Horican, after a tribe which may have lived there, because he felt the original name was too hard to pronounce.[citation needed]

The first European visitor to the area, Samuel de Champlain, noted the lake in his journal on July 3, 1609, but did not name it.[citation needed] In 1646, the French Canadian Jesuit missionary St. Isaac Jogues, the first European to view the lake, named it Lac du Saint-Sacrement (Lake of the Holy Sacrament), and its exit stream, La Chute ("The Fall").[7] The 1696 proposed war plan of John Nelson referred to the subject as "Lake Mohawk".[8]

On August 28, 1755, William Johnson led British colonial forces to occupy the area in the French and Indian War. He renamed the lake as Lake George for King George II.[9] On September 8, 1755 the Battle of Lake George was fought between the forces of Britain and France resulting in a strategic victory for the British and their Iroquois allies. After the battle, Johnson ordered the construction of a military fortification at the southern end of the lake. The fort was named Fort William Henry after the King's grandson Prince William Henry, a younger brother of the later King George III.

In September, the French responded by beginning construction of Fort Carillon, later called Fort Ticonderoga, on a point where La Chute enters Lake Champlain. These fortifications controlled the easy water route between Canada and colonial New York. A French army, and their native allies under general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm laid siege to Fort William Henry in 1757 and burned it down after the British surrender. During the British retreat to Fort Edward they were ambushed and massacred by natives allied to the French, in what would become known as The Massacre at Fort William Henry.

On March 13, 1758, an attempted attack on that fort by irregular forces led by Robert Rogers was one of the most daring raids of that war. The unorthodox (to Europeans) tactics of Rogers' Rangers are seen as inspiring the creation of similar forces in later conflicts—including the United States Army Rangers.

Lake George's key position on the Montreal–New York water route made possession of the forts at either end—particularly Ticonderoga—strategically crucial during the American Revolution.

Later in the war, British General John Burgoyne's decision to bypass the easy water route to the Hudson River that Lake George offered and, instead, attempt to reach the Hudson through the marshes and forests at the southern end of Lake Champlain, led to the British defeat at Saratoga.

Thomas Jefferson and James Madison traveled through Lake George during their Northern tour in 1791, sailing twenty five miles up to Lake Champlain.[10] On May 31, 1791, Thomas Jefferson wrote in a letter to his daughter, "Lake George is without comparison, the most beautiful water I ever saw; formed by a contour of mountains into a basin... finely interspersed with islands, its water limpid as crystal, and the mountain sides covered with rich groves... down to the water-edge: here and there precipices of rock to checker the scene and save it from monotony."

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Lake George was a common spot sought out by well-known artists, including Martin Johnson Heade, John F. Kensett, E. Charlton Fortune, Frank Vincent DuMond and Georgia O'Keeffe.

Ethan Allen accident

[edit]On October 2, 2005, at 2:55 p.m., the Ethan Allen, a 40-foot (12 m) glass-enclosed tourist boat carrying 47 passengers and operated by Shoreline Cruises, capsized during calm weather on the lake. According to reports from a local newspaper, 20 people (mostly senior citizens) died.

Initial reports indicated that the tour group was from Canada, but these reports were later found to be incorrect. It was later determined that the group was from the Trenton, Michigan, area on a week-long fall trip along the East Coast by bus and rail, organized by Trenton's parks and recreation department and arranged through a Canadian company. Police said they had never seen a disaster of this magnitude on the lake. The captain survived and cooperated with police.[11]

The National Transportation Safety Board investigation of the incident revealed that, although the boat was rated to carry 50 people when it was manufactured in 1966, subsequent alterations to the boat's design had greatly reduced its stability. At the time of the accident, the boat should have been rated to carry no more than 14 passengers. On February 5, 2007, the captain, Richard Paris, and the company that owned the boat, Shoreline Cruises, were indicted for having only one crew member aboard the boat. More serious charges were not filed because neither the captain nor the owners were aware they were violating safety standards.[12]

Character

[edit]Tourist destination

[edit]

Situated on the rail line halfway between New York City and Montreal, Lake George attracted the era's rich and famous by the late 19th and early 20th century. Members of the Roosevelt, van Rensselaer, Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Whitney families visited its shores. The Fort William Henry Hotel, in what is now Lake George Village, and The Sagamore in Bolton Landing opened at this time to serve tourists. The wealthiest visitors were more likely to stay with their peers at their private country estates.[citation needed]

The Silver Bay YMCA on Lake George was constructed in 1900. It has since evolved into a summer family camp, serving several hundred organizations and tourists every summer. Since 1913, on the East Shore of Lake George, YMCA Camp Chingachgook has hosted thousands of guests every summer.[citation needed]

Lake George is accessible by car via Interstate 87 and by air from Albany International Airport, which is about 45 miles (72 km) away.

Today, Lake George remains a tourism destination, resort center, and summer colony. Popular activities in the Lake George area include water sports, camping, amusement parks, hiking, paddling, and factory outlet shopping. Lake George is also toured through traditional steamboat rides on vessels such as Le Lac du Saint Sacrement and the Mohican, provided by the Lake George Steamboat Company.[13] One of the nation's oldest gatherings of hot air balloons occurs every September in nearby Queensbury.

Lake George is responsible for generating about $2 billion annually to the local region.[5]

Millionaires' Row

[edit]Millionaires' Row is the nickname of a stretch of Bolton Road (now Lake Shore Drive) on the west side of the lake where millionaires built mansions or resided during the summer months. Such notables as Spencer Trask, Katrina Trask, Edward M. Shepard, George Foster Peabody, Harold Pitcairn, Russell Cornell Leffingwell, Georgia O'Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, Marcella Sembrich, Charles Evans Hughes, Harry Kendall Thaw, Adolph Ochs, Louise Homer and Sidney Homer built or resided in palatial summer homes along Millionaires' Row. Although sometimes called "cottages" by their owners, these grand houses typically had dozens of bedrooms and more than 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2) of floor space.

Millionaire's Row differed markedly from the more rustic summer "camps" built by other wealthy Adirondack summer residents such as William West Durant and John D. Rockefeller. Unlike the log and timber structures at the camps, the houses of Millionaire's Row were built of stone and masonry in the Tudor Revival, Georgian Revival and Italianate styles.

Unlike their contemporaries in Newport and the Hamptons, which were built on tiny pieces of land, the cottages of Millionaires' Row were mansions in the true sense of the word. They were often built on hundreds of acres of pristine lakeside wilderness.

With the changing economic climate and the introduction of income tax, the mansions of Millionaires' Row became less sustainable by the 1930s. By the 1950s, with the advent of affordable auto and air travel, Lake George became more attractive to the growing middle class and less so to the "jet set". Most of the mansions of Millionaires' Row were torn down or turned into hotels and restaurants. Among the surviving mansions are Evelley, Halcyon, Sun Castle (Erlowest), Oak Lawn, Wikiosco, Green Harbour, Homeland, Cramer Point, Depe Dene, Cannon Point, Hermstone, Mohican Point, Villa Marie Antoinette's gatehouse, Three Brothers Island, Nirvana, and Wapanak.

Gallery

[edit]Photographs

[edit]-

Above Cook's Bay, facing south

-

View from The Sagamore in Bolton Landing

-

Lake George, on a foggy day.

-

View from Bolton Landing

-

View of southern end of Lake George.

-

Isles

-

View from Sabbath Day Point

-

An aerial view of Lake George, with Anthony's Nose and Roger's Rock visible

-

Aerial panorama of Lake George at sunrise in late September

Paintings

[edit]-

John Frederick Kensett - Lake George - Brooklyn Museum

-

John William Casilear - - Lake George - Brooklyn Museum

-

Lake George - John F. Kensett, Hudson River School

-

Régis François Gignoux - Lake George - Brooklyn Museum

Videos

[edit]-

View of Lake George from Buck Mountain in Fort Ann, NY March 31, 2018

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Lake George". Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza.

- ^ See:

- Bolton Landing Chamber of Commerce, Visit Lake George Archived 2008-05-18 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved May 12, 2008

- Albany International Airport, AIRPORT GALLERY FEATURES LAKE GEORGE "QUEEN OF AMERICAN LAKES" Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2008

- The Hyde Collection, Painting Lake George: 1774 - 1900 Archived 2010-11-25 at the Wayback Machine, September, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2008; Erin Budis Coe and Gwendolyn Owens,

- Painting Lake George 1774-1900, Syracuse University Press, 2005

- ^ "Lake George". dec.ny.gov. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ "Lake George Water Quality | Lake George Association". lakegeorgeassociation.org. Retrieved 2024-08-01.

- ^ a b Williams, Stephen (August 24, 2019). "Advanced research making Lake George "smartest" in world". dailygazette.com. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- ^ "Invasive Species". Lake George Association.

- ^ "Lake George Historical Society". lakegeorgehistorical.org. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2010-09-05.

- ^ "America and West Indies: September 1696, 21-25." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 15, 1696-1697. Ed. J W Fortescue. London: His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1904. p. 136. British History Online Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 136.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (21 May 1791). "I. Jefferson's Journal of the Tour, [21 May–10 June 1791]". National Archives.

- ^ The Albany Times Union, TRAGEDY ON LAKE GEORGE, Special Report; retrieved May 12, 2008.

- ^ "Captain Indicted in Fatal Boat Accident". Associated Press. February 5, 2007.

- ^ Ambrosino, Jonathan (January 1, 2006). An Organ Atlas of the Capital District of New York State. OHS Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0913499733.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |